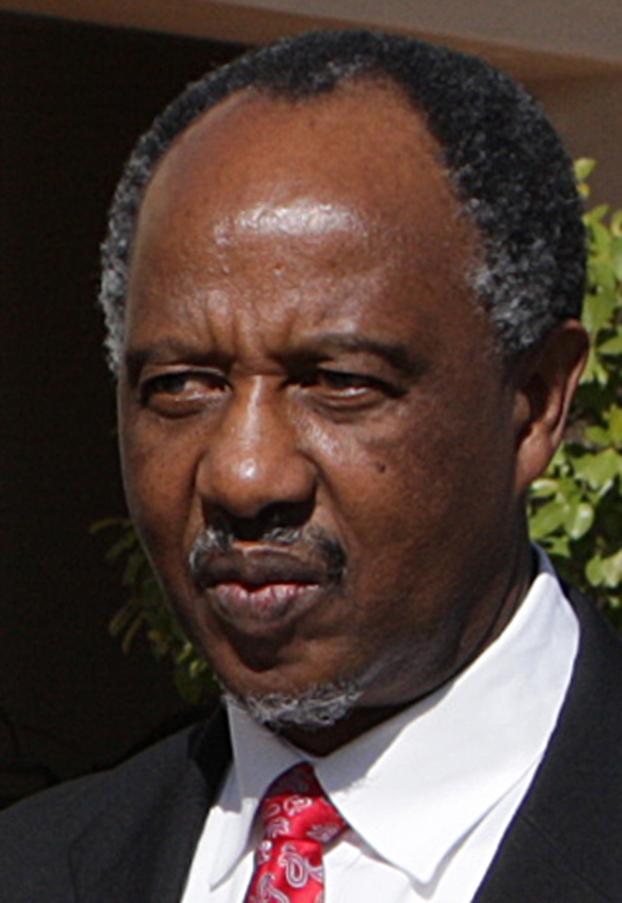

by beCause Global Associate, Advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza, Chairman Africa Dispute Resolution Company, acting judge High Court of South Africa, who served as Commissioner on Truth & Reconciliation Commission and President of Black Lawyers Association: transcript of remarks he gave at 4th International Africa Peace And Conflict Resolution Conference *** It is my singular pleasure and honour to address an occasion such as this, when luminaries from the African continent have been marshalled for the next TWO days to be here in JOHANNESBURG, a city which the Mothers and Fathers thereof, like to call a “world class African city”, whatever they mean by that. The Conference is organized by organizations BOTH of which are in the business of PROMOTING PEACE and seeking to RESOLVE Conflicts in the African Continent.

by beCause Global Associate, Advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza, Chairman Africa Dispute Resolution Company, acting judge High Court of South Africa, who served as Commissioner on Truth & Reconciliation Commission and President of Black Lawyers Association: transcript of remarks he gave at 4th International Africa Peace And Conflict Resolution Conference *** It is my singular pleasure and honour to address an occasion such as this, when luminaries from the African continent have been marshalled for the next TWO days to be here in JOHANNESBURG, a city which the Mothers and Fathers thereof, like to call a “world class African city”, whatever they mean by that. The Conference is organized by organizations BOTH of which are in the business of PROMOTING PEACE and seeking to RESOLVE Conflicts in the African Continent.

It is not without reason that these organisations would want to promote peace in Africa. Progress and prosperity require a CONFLICT- free society anywhere in the world. Justice, in all its manifestations, whether transitional justice or traditional criminal or civil justice, or restorative justice, – all of the manifestations of a single concept, justice—-thrives only in, societies and communities that can quickly resolve conflicts, societies that have well established mechanisms and processes that can guarantee delivery of justice swiftly, cost-effectively and to the largest number of people possible, in any one community, most often the poorest, the vulnerable and the marginalized of our societies.

- CONFLICT IN THE CONTINENT

African societies, since liberation from colonialism, from 1959 (Ghana) to 1994 (South Africa) are now at various stages of development in their various struggles to be democracies. Some of them have gone through terrible military coups that have ushered in repressive societies, where human rights have taken a back seat, and where the citizens and people in those countries have felt that they are worse off—if that is even conceivable—-than they were during colonial rule.

In some societies, people have overthrown horrible dictatorships and the justice question in those societies, the ones that have emerged from repression, always is a transitional justice question.

Briefly, transitional justice addresses the critical questions of what happens in society at the end of hostilities. What scenarios present themselves at the end of a conflict in a particular society? What different solutions are applicable to different situations where societies emerging from repression seek ways of restoring democracy, human rights, rule of law, peace, reconstruction and development? What happens, if anything, in these emerging societies to perpetrators of gross violation of human rights? What punishment, if any, must be meted out, by whom, and how? Is it possible, in any event, to do so? If perpetrators are not punished, what happens to the rule of law? What message is sent to criminals world-wide if heinous crimes cannot be punished? What are the constraints? Is failure to prosecute post-conflict criminals not promotive of a culture of impunity? What are the implications of impunity to democratic and orderly society?

Victims: Is there a need to compensate victims, to rehabilitate them, to re-integrate them into society? What about reparations? How critical is it, for the transition period, for truth about the past to come out, and for what purpose? What situations call for criminal prosecutions? Are there any situations imaginable where criminal prosecutions are not possible/desirable/necessary? What are alternatives to prosecutions and how viable are those? In each of the scenarios, what really accords with justice? Doesn’t justice – and has it not been so throughout time – prescribe an eye for an eye? Is not, in the final instance, justice predicated on the simple principle that every violation calls for punishment?[1]

The answer to all these questions above would fall within the province of the discipline of transitional justice, whose primary focus is to determine what solution is best in accordance with justice in each post-conflict situation in societies that endeavor to return to normalcy.

Concerns of a society in transition from a repressive dictatorship to democracy are issues of justice, truth, peace, reconciliation, human rights, nation building, reconstruction of society and the elimination of a culture of impunity.

Truth, justice and reconciliation sometimes find themselves at odd with one another. Those who would rather criminals were prosecuted run the risk of never being able to arrive at the truth of what happened. Courts are, by all accounts, not the best mechanism at discovering the truth. The South African TRC is replete with case studies that show that truth[2] was only revealed to victims through the amnesty process.[3] Criminal justice processes in the past had dismally failed to place the victims in any clearer light as to what had happened. The TRC process succeeded where that process had failed, albeit, as quid prop quo, it meant the perpetrators escaped criminal prosecution and civil liability.[4]

Further, the incoming regime may be loathe to prosecute because of a number of constraints including:

- Lack of political will;

- Lack of capability and resources;

- Length of time that prosecutions would take;

- Threat of rebellion by former security personnel if they are still powerful;

- The old regime’s capacity to delay prosecutions.

These constraints apply even in post-conflict situations where you have “clear” victors. In Rwanda, for example, constraints are some of the above. There are also problems – whether prosecutions are in the tribunal or in the domestic courts – like costs, ineptitude, slow pace, corruption, ethno-racism, no real infra-structure, no jurisprudence to inform legislation to try genocides. There is also the undermining of the criminal justice system principle of “justice delayed is justice denied”, flouting of the principle of presumption of innocence insofar as “suspects” are kept in “hell-holes” for endless periods of time without ever having the opportunity to appear before a tribunal or court, and so on.

Further, prosecutions may well eliminate all chances of reconciliation. Perpetrators may well take the view, after prosecutions and sentence, that they have no debt to pay anymore, that they do not need to be reconciled with their victims. If – as some of them sometimes argue – they believed in the “rightness” of their cause in their perpetration of heinous crimes, they may be filled with such resentment in being prosecuted that no chance of reconciliation would be possible, let alone national unity, and reconstruction of society.

On the other hand, some victims may well justifiably feel that prosecutions are absolutely necessary. In Rwanda, for example, prosecutions are justified on the basis that they provide justice to the victims. Even with all the constraints, prosecutions have a symbolic value. They reduce any potential for a culture of impunity taking root.[5]

ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION

The topic I am being asked to address, however, assumes stable societies and democracies where the Rule of Law obtains, where court systems are operational, credible and legitimate and where the debate is not so much what one does in order to get OPTIMAL justice, but what OPTIONS are available, for maximization of the benefits of a justice system that is geared to deliver justice by making access to justice possible to a great number of people.

Simply put, does our justice system, hardly ever utilize alternative ways of justice delivery, suitable for today’s societies? Do our civil justice systems in the Continent respond adequately to the demands of commercial activity, justice, legal certainty, swiftness of delivery of judgments, access to justice by the vast majorities of our societies?

I, as a trained and qualified Arbitrator, and as a trained and qualified Commercial Mediator, and a lawyer who has been in the practice of the law for the last 30 odd years, and one who has acted as a Judge in the High Court and in the Labour Courts, have no hesitation in saying the ONLY way for a swift, cost-effective way to deliver justice, especially for the greatest majority of the people – the poor, the marginalized and the vulnerable of our societies – is by an unwavering commitment by our Government to the implementation of Court based or annexed mediation process, starting with conciliation procedures. I agree, as I have done for almost a decade now, that conciliation, mediation and arbitration should be used more often, by a justice system that does not simply pay lip service to the notion of the efficacy of ADR mechanisms.

DEFINITION OF MEDIATION

It is proper to define mediation and conciliation, and for that I draw on the King III Report on Corporate Governance: ‘Mediation may be defined as a process where parties in dispute involve the services of an acceptable, impartial and neutral third party to assist them in negotiating a resolution to their dispute, by way of a settlement agreement. The mediator has no independent authority and does not render a decision. All decision-making powers in regard to the dispute remain with the parties. Mediation is a voluntary process both in its initiation, its continuation and its conclusion’.[6]

ACCESS TO JUSTICE IN THE WORLD

As practitioners of law, we know that most matters settle on the proverbial ‘steps of the court’ after the matter has been allocated a trial date, court room and a presiding officer well before the date. We also know that the cost of litigation is often out of proportion to the quantum in dispute.

THE CRISIS IN WORLD LEGAL SYSTEMS

Some might argue that the South African court system is not managed efficiently, and that this is the motivation animating any policy in favour of the introduction of court based mediation. I prefer not to go into this argument, save to cite Mervyn King SC’s chairman’s preface to the King III Report on Corporate Governance p 16: It is accepted around the world that ADR is not a reflection on a judicial system of any country, but that it has become an important element of good governance.

Far more important, is that world justice systems are experiencing the same pressures and the same structural conditions and challenges. These seem to suggest that citizens and lawyers are placing excessive demands on court systems, and that some of the demands may stem from aspects such as consumerism, consumer protection, increased rights consciousness and litigiousness in many societies. This factual observation notes these social phenomena for their impact on the justice system, and does not express on them a value judgment.

EXCESSIVE DEMANDS ON COURT SYSTEMS

The courts function in increasingly consumerism and consumer protection, both of which are at least to some extent a good thing. However, the effect is that greater demands are made upon the courts for enforcement and relief.

A first instance is debt review applications under the National Credit Act 34 of 2005 (NCR). Currently, the courts are facing approximately 7 000 new applications every month, and the backlog of pending applications is upwards of 200 000.00. Reports suggest that magistrates across the country are desperate for an alternative way of dealing with these matters. Despite its provision for alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms, the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008 is likely to result in increased claims on the resources of the court, and it is therefore necessary that the National Consumer Commission and courts should be astute to prevent a recurrence of the experience under the NCR.

Our experience as law and ADR practitioners shows a large number of cases where parties enter into litigation without a proper consideration of the disadvantages or of alternatives. Often clients are not advised regarding the availability of more time and cost efficient ways of resolving disputes.

These may be some of the conditions leading to the statement of Lord Justice Woolf in the English case of Cowl v Plymouth City Council that: ‘Today sufficient should be known about ADR to make the failure to adopt it, in particular where public money is involved, indefensible’.[7]

CASES BELONGING OUTSIDE COURT

Mediation is not designed to supplant litigation. The court has a constitutional duty to dispense justice. The court also has a right to determine legal rights through the interpretation of law. Thus litigation is a necessary and vital social function with a number of benefits, including the development of our system of constitutional principles and general jurisprudence, the structure of precedent and case authority and the disposal of cases requiring complex legal reasoning, and thus the natural province of the courts.

Litigation will also be necessary for parties, particularly where one of them is a large public or private sector institution, requiring a determination on a matter of policy or principle.

So much of what happens in court concerns questions of basic existence – of survival: whether it is the right to a house, to health, to potable water or to some other basic human need. National residents have the right to pursue these issues in the context of a society that honours the right to dignity in a constitutional and democratic state,[8] in particular the right of access to justice enshrined in section 34 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act 108 of 1996 to the effect that: ‘Everyone has the right to have any dispute that can be resolved by the application of law decided in a fair public hearing before a court or, where appropriate, another independent and impartial tribunal or forum’.

The question is merely whether the resulting cases necessarily must be resolved through the judicial process. We would suggest that the answer is no. In this connection, I am reminded of the words of the London based Centre for Effective Dispute Resolution[9] to the effect that: ‘No easy assumptions or assertions can be made over whether or not a case is unsuitable for mediation. It is wise to assume that practically every case is likely to be suitable for mediation at some time in its life cycle and that the right question to ask is not “is it suitable” but “is it ready?”.

This observation is especially relevant to disputes that fit one or more of the following descriptions: simple, minor, routine, repetitive and homogeneous. Court based mediation is therefore a process by which mediation works in tandem with the courts at multiple touch points, with cases revolving variously in and out of court and mediation, in such a way as to assist the court to perform its adjudication function effectively.

THE COST OF DOING BUSINESS

To the extent that resolution of disputes occurs within the context of the challenges faced by our system of justice, the incremental cost of doing business in South Africa may become high in combination with other factors. The cost of the actual legal process, though high, may not be the most significant. The attendant costs such as broken business relationships, frustration within a company, loss of focus and the loss of executive time and capacity to perform their actual function are more expensive[10]. Justice Kiryabwire reports improved performance in the stock market performance and in inward foreign investment as a result of the Uganda court annexed mediation programme.

Of course, it is not the function of a gathering such as this to be concerned about the cost of doing business, even in its relation to the creation of a business environment that is conducive to international investment. However, we are correctly concerned with the problem of access to justice for business. Though less constrained by ills such as poverty and illiteracy, the business sector is also challenged by the issue of access to justice; albeit that this in a very different form, without the bone crushing social limitations, and to a degree that is clearly distinguishable from that of the old age pensioner. The time and money cost barriers simply become a slightly less serious matter, and less prohibitive in the corporate. However, one cannot gainsay the fact of their being a reality.

COURT BASED MEDIATION IN THE WORLD AND IN SOUTH AFRICA

Recognising the excessive demands upon them, and the constraints facing them, legal systems across the globe are turning to court based mediation in their numbers.

Thus key instances can be found in Africa [Uganda, Nigeria, Namibia and Lesotho], Europe [England, Holland and Italy], Asia [India, China, Hong Kong, Russia and Singapore] and the Americas [Brazil, Canada and the United States of America]. At least fifteen of the states in America – including Alabama, California, Florida, Maryland, North Carolina, Indiana and Texas – have taken this direction. Ontario is taking the lead in Canada. Uganda has had a successful scheme for a time. Namibia is at an advanced stage of implementation. The Lesotho authorities are thinking seriously in this direction. What we have is clear evidence of forward thinking states taking a shared approach to a worldwide challenge.[11]

THE INTRODUCTION MECHANISM

Comparative experience [Uganda, India, Texas, Italy and Russia] suggests that legislation and rules of court [Hong Kong and South Africa] are the standard means for prescribing court based mediation.

The South African example includes both the by now well-known instance of the new rules of the regional and district magistrate’s courts, and the recent passing of a Rule, formulated by the Rules Board for the Courts of Law that now allows for court connected mediation. Hong Kong handled the matter by way of Practice Directive 31.[12] The Russian approach has used legislation.[13]

SANCTIONS

As can be seen from experience elsewhere [Hong Kong, Texas, Italy, Uganda, India], the customary sanctions for failure to mediate include refusal to set the matter down or the de-prioritisation of the case for allocation of a court date.

We hear also of examples of costs sanctions for failure to mediate, Italy being one. Examples apparently exist of conduct standards being applied.[14] And so, parties may be required to meet criteria of genuine effort, reasonable attempt, satisfactory negotiation and good faith efforts. To be fair, the good faith requirement appears to have little favour with the courts of Texas,[15] apparently because it entails excessive ‘judicial intrusion’ into mediations, and thus threatens the ‘fundamental rights of the parties’.

COMPULSORY MEDIATION

The question whether mediation should be made a compulsory step in the process has been debated in many jurisdictions across the globe. In the UK, mediation was introduced a decade ago. It was made voluntary with judicial encouragement through the development of case law. The result is that only 5% of cases were referred to mediation.

In contrast the model in the USA, and more specifically the Texas model, is a compulsory court-ordered model. Judges can be requested to order the parties to mediation in the event that any party refuses to go. This has resulted in a more structured approach to the use of mediation as an integral part of the litigation process.[16] Uganda based associates tells us that cases lodged in court for several months were resolved within weeks as a result of the introduction of court annexed commercial mediation, leading to great satisfaction from affected chief executives.

It is clear that no court can compel the parties to mediate. However, it can compel them to take part in a mediation process. Lawyers and their clients are not aware of the benefits of mediation. ‘Forcing’ them to take part in the process is likely to result in the growth of the use mediation process.[17]

The ready conclusion is that the introduction of mandatory mediation is better than leaving the matter to us the lawyers. This is certainly the approach in jurisdictions such as Hong Kong, Italy and the Netherlands. In Texas, the courts require, albeit under empowering legislation, pre-trial mediation in every case. The Texas courts almost never grant an objection to court-ordered mediation.[18] The author .concludes on p 4 of his article, that this is because ‘the judges like the mediation process and feel it works’. Mr Abrams also reports the interesting experience that the more Texas lawyers experience ADR, the more they choose to use it on a voluntary basis; and that is true of major Texas cities such as Austin, Dallas, Houston, the Capitol, San Antonio and Corpus Christi.[19]

Reporting the considerable growth in mediation laws in countries such as Argentina and many others, he expresses the opinion that: ‘It just seems like too much of a coincidence that most, if not all, of this rapid expansion began soon after significant use of compulsory mediation…Perhaps I’m biased but I believe compulsory mediation played a big role in the expansion of mediation and conventional mediation’.[20]

The South African Ministry of Justice [and Correctional Services, as it is today called], by “bending at the knees”, and ostensibly succumbing to pressure from interested parties, possibly from the profession [and some or a significant number of the judges?], has, in my very humble and respectful opinion, lost a golden opportunity in not opting for, and later enforcing, a Rule for a compulsory reference of matters to mediation at as earliest stages of litigation as possible. Nor am I persuaded, as according to received wisdom, the State Law Advisers were, that such a Rule would never have passed constitutional muster—if challenged.

STAGE OF REFERRAL

There is a view that a case should only be referred to mediation after litis contestatio and after discovery, since only then will the parties have a full grasp of all the issues in the case.

The counter view is that mediation or its shorter version, conciliation, can play a substantial role in reducing the issues in dispute and facilitate the early exchange of information that could lead to early settlement of the case. Therefore, there is logic in earlier referral of the case.

The middle road provides for the referral of a case to conciliation on notice of intention to defend or oppose, and to mediation upon a matter being entered on the continuous roll.

Conciliations, a shorter and more robust process, would in this context be used both to explore early settlement of cases and play the role of a case management meeting. In this conciliation process, the mediator is tasked with exploring specifically three things: the early and informal exchange of documents and information, mechanisms for narrowing the areas of dispute, and finally agreement on the further conduct of the matter. This could, in the absence of a settlement, allow the case to be ready for a full mediation or a hearing a lot sooner with a focus on what is really in dispute.

CASE CATEGORIES

International experience shows, despite the view that mediation is more applicable in certain categories of cases, such as personal injury and family disputes, any kind of dispute can be settled by way of mediation.

In some jurisdictions, the parties can object to a case being referred to mediation, leaving the court the discretion to uphold or dismiss such an application. If regard is had to the general objections that are raised in the jurisdiction of Texas such as: that there is no likelihood of success, a party cannot afford the mediation or the case is not ready for mediation, it is clear that lawyers are capable of using any reason to avoid.[21] In any case, these applications will likely only add to the burden on the court’s time.

Since the referral to conciliation will also serve the purpose of a case management meeting which will benefit the court process, the argument is fulsome that all cases should be referred for at least the initial conciliation procedure.

JUDICIAL DIRECTION TO MEDIATE

Since it is the court’s duty to ensure the expeditious and cost-effective resolution of disputes, and since in most jurisdiction it is in fact the court that directs parties to mediation, the South African initiative should provide that a presiding officer, whether on application or mero motu, may instruct the registrar or clerk of the court to refer the matter to mediation for a conciliation or mediation meeting. This is widely recognised in the theory and practice of the Texas Supreme Court.

Time and space do not allow a further exposure of why I argue that ADR mechanisms are what the African continent, and indeed the world, now needs, and will need for a long time in the future. I would have liked to talk, as I have written elsewhere, about mediation fees, the duty to inform, the centrality of confidentiality, especially in conciliation and mediation, service standards, and so on. Perhaps those are aspects that we will debate during the interactive stage.

CONCLUSION

Lest it be misconstrued that CBM/CAM (Court Based Mediation or Court Annexed Mediation) is the only ADR mechanism I agitate for, I should correct that misapprehension, and emphasise that I have the highest regard for Arbitration as an ADR mechanism. It has become the preferred method of resolving patently adversarial disputes, for which conciliation and or mediation are either unsuitable or have failed to resolve the respective disputes. Arbitration has been the preferred dispute resolution method, after mediation has not succeeded in resolving a particular dispute, precisely because it is quicker than ordinary Court processes, is more cost effective and in that way ensures that CEO’s are engaged in the business of business, rather than in spending hours/days/weeks/months on end, held up in Courts.

The further point I want to make is that ADR mechanisms are not, contrary to popular belief and propaganda by my learned colleagues in the profession, an attempt to emasculate the Constitution in the RSA and to privatise the civil justice system.

There is an acceptance, by progressives in the profession, that in the case of the RSA, there is a need for commerce, in the main, to be impacted upon by the foundational values embedded in our Constitution, 108 of 1996, especially those rights and obligations entrenched in Chapter 2 thereof, and the values of ubuntu, good faith in contracting, and fairness.

In the Arbitration Forum, a forerunner of EQUILLORE, a dispute resolution company that I chair, as early as a dozen years ago, whenever Counsel raised a constitutional argument, we immediately referred the matter to the High Court for the adjudication of the constitutional point raised by either Counsel. One such case was Engelbrecht v Road Accident Fund and Another[22], a case that went all the way to the Constitutional Court via the Supreme Court of Appeal, after the initial referral, to the Cape High Court, by an Arbitrator hearing the matter in the Arbitration Forum/Equillore.

The accusation, therefore, that ADR mechanisms will insulate commerce from the impact of the Constitution, and that large scale usage of ADR will amount to the privatisation of the civil justice system cannot stand in light of this evidence.[23]

As I close, I would very much like to quote an apposite statement, especially at a Conference put together by two organisations committed to peacemaking. The quote is attributed to Abraham Lincoln, the US President who was tragically assassinated on Good Friday, 14th April, 1865. He is quoted to have said the following:

“Discourage litigation. Persuade your neighbours to compromise whenever you can. Point out to them how the nominal winner is often a real loser—–in fees, expenses, and waste of time. As a peacemaker, the lawyer has a superior opportunity of being a good man. There will still be business enough.”—Abraham Lincoln.

Need I say more? We will have to redefine what “progress” means if a century later after those words were expressed, we still have not seen the light.

It merely remains for me to wish this Conference well, and to hope that the debates over the next two days will be robust, even as they are constructive and fruitful, and that all delegates will be better informed about conflict resolution and peacemaking than they were when they came. Please also find time to enjoy the thrills of the …you have said it…”world class African city”

********

[1] NTSEBEZA, The relevance of Transitional Justice as a Discipline, WSU LAW JOURNAL 2006, pp 94-97

[2] Eg. in CHILE and in the various coups in Nigeria that followed “civilian” rule after another coup eg. Babanginda toppling the Cevshan regime to whom Obasanjo had handed power.

[3] Or as near to it as can be arrived at

[4] One of whose requirements for a successful application was “full disclosure”.

[5] Tbid pp 95-96

[6] Institute of Directors of Southern Africa Johannesburg (2009) 122.

[7] [2001] ADR.L.R. 12/14.

[8] Refer generally to Khanya B Motshabi ‘The Case for Court Based Mediation’ 21 October 2010 Cape Times 12.

[9] Court Referred ADR: A Guide to the Judiciary CEDR 2nd Edition London 2003 on p 9]

[10] See also, for similar points and for the experience in Scotland, John Sturrock ‘The Role of Mediation in a Modern Civil Justice System’ Undated Mediate.com Paper on File with the Speaker]. See too, the article by Justice Geoffrey W M Kiryabwire, Judge of the Commercial Court Division of the High Court of Uganda and a former insurance company chief executive, ‘Mediation of Corporate Governance Disputes through Court Annexed Mediation’ Unpublished Paper on File with the Speaker.

[11] For further on the Texas experience specifically, see generally the very helpful article by Jeffry S Abrams Compulsory Mediation: The Texas Experience Undated Unpublished Paper on File with the Speaker]. On the Uganda situation, see the instructive case study by Justice Geoffrey W M Kiryabwire [‘Mediation of Corporate Governance Disputes through Court Annexed Mediation’ Undated and Unpublished Paper on File with the Speaker, and generally, Professor Don Peters ‘Court-Connected Mediation in Florida and the USA’ (2004) in a debate on ‘Justice for the Poor? Could Mandatory Mediation Offer Access for Justice and the Protection of the Law to All Citizens’ Summary Notes from the 12 June Goedgedacht Forum for Social Reflection.

[12] ONC Lawyers (2010) July 1.

[13] The Russian experience is described in Elena Makarova ‘Russia: New Regulation of Mediation’ (2010) 3 September Commercial Dispute Resolution 1.

[14] Presentation by Professor Laurence Boulle on ‘Corporate Governance and ADR: What’s Happening, Where and Why’ (2011) March Tomorrow’s Leaders Convention, Sandton]

[15] Brett Goodman ‘Are Parties Required to Negotiate in Good Faith’ 2011 Disputing 2.

[16] Brett Goodman ‘Can a Court Impose Sanctions for Failing to Appear at Court-Ordered Mediation?’ 2010 Disputing 3 June & Karl Bayer ‘’Can I Object to Court-Ordered Mediation?’ 2010 Disputing 10 June

[17] [See also Justice SB Sinha ‘ADR and Access to Justice: Issues and Perspectives’, referred to earlier especially pp 13-18.

[18] ‘Compulsory Mediation: The Texas Experience’ Undated and Unpublished Paper on File with the Speaker.

[19] P 2

[20] P 9

[21] Brett Goodman ‘Can a Court Impose Sanctions for Failing to Appear at Court-Ordered Mediation?’ (2011) Disputing 3 June & Karl Bayer ‘’Can I Object to Court-Ordered Mediation?’ (2011) Disputing 10 June.

[22] 2007 (6) SA 96 (CC)

[23] I had represented the Road Accident Fund in the arbitration before the Arbitration Forum. I was not yet Chairman the Forum at the time.